- Home

- Laura Tucker

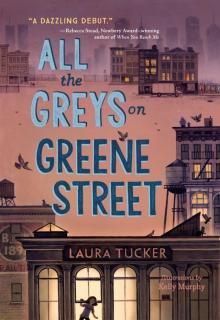

All the Greys on Greene Street

All the Greys on Greene Street Read online

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

New York

First published in the United States of America by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2019

Text copyright © 2019 by Laura Tucker

Illustration copyright © 2019 by Kelly Murphy

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Visit us online at penguinrandomhouse.com

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA IS AVAILABLE.

Ebook ISBN 9780451479549

Version_1

For Doug

this and everything

* * *

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Mayday

Mom Habitat

Twenty-Seven Kisses

Few, Several, Many

Smudge

Purr

Wake Up!

Sir

Five for a Dollar

Still in Love

A Long Way Down

The Last of the Heroes

Reach Out and Touch Someone

Big Ideas

Wild Times

A Big Fat Nothing

Just a Sketch

Kind of Suspicious

Fake

Butterflies

Free Falling

Saving Lambie

Field of Reeds

No Answer

Bunny Mummy

Draw What You See

Leave It

Miz Monochrome

No Éclairs

Outside, Looking In

How I Think

Just a Kid

And They Danced by the Light of the Moon

For a Ghost

Saturday (Again)

Double Trouble

Some Island

Trash

Notgun

Rear Window

Watch the Blues

Sick

The Game

Slow Time

The Walk Back

Maybe

Climb

What I Saw

Proof

Make Something

Blur

The Making of a Brave Man

Ours

The Meaning of Mayday

Two Gifts

Brooklyn

Off the Ground

Something to Look Forward To

The Blink of Love

Away

Note to the Reader

Acknowledgments

About the Author

MAYDAY

May Day is the first day of May.

“Mayday” is a radio signal used by ships and aircraft in distress.

This spring, May Day was the first day that my mom didn’t get out of bed.

Unfortunately but maybe not coincidentally, it was also one week to the day of my dad’s disappearance.

MOM HABITAT

My mom woke up when I kissed her forehead hello. “How was school?”

It was almost four in the afternoon.

“Okay.” I scratched the back of my leg with my sneaker. “Did you work late? Is that why you’re still in bed?”

My mom makes sculptures. Sometimes I’d surprise her still at her worktable when I came out of my room to go to school in the morning.

She shook her head, silvery grey strands moving against the pillow in the red darkness of her hair. Then she closed her eyes again.

“I guess I just didn’t feel like getting up today.”

My stomach tilted. It set itself right again when she patted the spot next to her on the bed.

“Thanks for getting my stuff, babe.”

That morning, when I’d gone in to kiss her goodbye, she’d asked me to bring her two packs of cigarettes, a can of peanuts, and a six-pack of Tab from Mr. G who owns the Optimo on Broadway. Mr. G told me scientists think that Tab causes cancer, which makes sense to me. If cancer tastes like something, it’s probably room-temperature Tab.

I sat down, and my mom scratched my back, hard, the way I like it. I pushed back against her hand like a cat.

“You want to watch something?” I asked her. Sometimes when she gets like this, she likes to watch TV, but this time she only shook her head.

“Are you going to get up now?”

“I don’t think so. Not yet. Take money off my dresser later, if you want to order in. This isn’t going to be forever, honey. It’s just that right now I’m . . .”

She didn’t tell me what she was right now, but pulled the comforter back so I could get in. “Vouley Voo?”

That was her making a joke. Our nickname for the woman my dad ran off with is Vouley Voo. Her real name is Clothilde, and she’s French-from-France, which was one of the reasons he’d gone there. My dad’s an art restorer. He used to fix damaged artwork in his studio on the floor above us. But in the seven days since he’d been gone, his partner, Apollo, had taken over most of the work.

Apollo has a Greek name like me, even though he’s Polish. My name, Olympia, comes from a painting by Manet, who was French like Vouley Voo. The painting caused a tremendous scandal in 1865, the first time it was shown—not because Olympia is nude, but because of the way she’s looking straight out at the viewer. I guess nudes weren’t supposed to look back.

My mom opened her arms and I lay down so she could spoon me, leaving my feet sticking out from under the covers because I was still wearing my sneakers. My mom doesn’t care about things like that, but I do.

We lay there together in the half-dark for a while, and I let myself be comforted by the warmth of her body and the mom-habitat smell of the bed.

When I could feel that she was asleep again, I rolled out from under her arm and went back out into the big room where it was still light.

TWENTY-SEVEN KISSES

Our loft is in a building that used to be a factory. My parents’ bedroom has a door. The bathroom does, too. My bedroom just has a curtain.

The rest of the apartment is the big room. I learned to ride a bike in there.

I used to wish we lived in a normal house, with a living room and a dining room and a backyard and a doorbell, except there’s no way my parents would ever live in a house like that. Artists need lots of space and light.

Lofts have both, and they’re cheap for New York, but to live in one, you have to prove that there’s an artist-in-residence. Our artist-in-residence is my mom.

I wandered over to her workbench, an enormous stained wooden slab propped up on sawhorses between the windows on the Greene Street side of the loft. As I leaned in to see if she’d made anything new, I kept my hands by my sides—an old habit, to remind me not to touch.

The pieces were all connected, balancing at impossible angles. I k

new that when she was done, the way they were positioned would tell a story. I’d already seen the button marked PUSH, strong black letters painted onto the old-fashioned green glass, wires trailing from the back of the panel like hair. I’d seen the used tea bag, stained an antique yellow, that she’d cut open and embroidered with wandering stitches so minuscule you couldn’t imagine the needle small enough to make them. And I’d seen the tiny fan, woven like cloth out of ordinary dressmaker’s pins, waiting on a tattered piece of red flannel. I still couldn’t figure out how she’d made it.

Not everything was small. There was an enameled sign from a store that used to sell ladies’ dresses, hammered almost beyond recognition into a rough crumple and slashed with paint. But she hadn’t added anything new in a while.

I wouldn’t say I was worried. Still, the fact that she wasn’t working wasn’t great.

I pushed the button on the answering machine on the windowsill, mostly to hear my dad’s recorded voice boom out through the loft, telling people to leave a message like the past week had never happened.

There were two new messages. The first one was from my mom’s new gallerist: “Hello, darling. Checking in.” The second person hung up, but not before the machine recorded them breathing for a while. In the movies, a heavy breather is usually a creeper, but this sounded more to me like someone thinking about what they wanted to say before deciding they didn’t want to say it.

Restless, I looked around the big room for something to draw. The late afternoon sunlight slanted through the enormous windows, cutting across the worn wood floorboards on a diagonal. Drawing light through glass is difficult, but my dad says you won’t get better if you don’t push yourself. I opened up my notebook and squinted like he taught me, reducing the shadows to a puzzle of light and dark shapes.

Apollo gave me this notebook, the kind that real artists use; he also buys me Blackwing 602 pencils, which are the best. He’s always trying to get me to use color, but I’ve got enough on my plate with grey for now.

I sharpened my Blackwing and began roughing out the shaky outline of the sunlight on the floor, the smudged shadow where the window was dirty. Then I built on the network of loose lines I’d sketched, making them stronger and darker as the composition took shape under my fingers.

My dad had left a week ago. In the middle of the night. Without saying anything to anyone.

My pencil moved faster as I marked out the shape of a muscular tabby cat with thick black stripes, lounging like a tiger in the center of the page. I want a kitten, but my dad says that people are barely allowed in our building, let alone animals, so I draw a lot of cats.

Everyone had been surprised by how well I’d taken my dad’s sudden disappearance. But the morning after he left, I’d gone to pour myself a glass of orange juice, just like I did every day. Stuck to the bottom of the container, I had found a piece of paper, precisely folded to fit underneath.

It was a note from my dad.

Ollie, his note read. There’s something I’ve got to do.

Not everyone agrees that it’s the right thing, which is why it might be a little while before I can call.

In the meantime, you’re going to have to give yourself twenty-seven kisses every morning and tell yourself that I love you. (That part won’t be hard because you know it’s true.)

P.S. Don’t tell ANYONE about this note and get rid of it ASAP.

After adding a little shade to the triangle of the tabby’s white chin, I made myself stop before I ruined the whole drawing. I looked critically at it. It was good—good enough to give to Mr. G, who trades me a Goldenberg’s Peanut Chew every couple of weeks for a piece of original art, which he hangs next to the Spectacular Landscapes of Iran calendar that his cousin sends him from Tehran.

I had destroyed my dad’s note by tearing it into confetti, like Lily Holbrook in Eve’s Vengeance. Except that I flushed the pieces down the toilet, and they would never have shown a toilet flushing onscreen in the fifties.

I missed him, but I was trying to be patient; I knew he’d call when he could.

Except now that my mom had stopped getting out of bed, I found myself wishing he’d call sooner rather than later.

FEW, SEVERAL, MANY

“Bobby Sands is going to die,” Alex told me.

The garbage on my block is usually pretty interesting. For example, there are always these long cardboard tubes outside the United Thread factory that make good lightsabers. Alex and Richard were dueling with two of them on Monday morning outside my building when I came out to walk to school. They stopped when they saw me come out because they think playing Star Wars is babyish now.

I was impressed. Usually they forget that I’m someone to be embarrassed in front of.

I’ve known Alex forever. He lives a block away, and we walk to school together most days. There aren’t that many kids in SoHo, so the public school closest to us is in the West Village. Richard lives closer to school, but he’d spent the night at Alex’s house.

It had looked warmer out the window than it actually was, and I shivered. Alex pulled off the blue sweatshirt I knew his mom, Linda, had made him tie around his waist before he left. When I put it on, the sleeves came down over my hands.

“Sweater weather,” Richard said happily.

Spring comes all at once in New York. One day, the sun comes out and the birds start chirping and the trees in Washington Square Park get flowers. A month later, the pavement melts and everything starts smelling like the greasy stain below the dumpster outside C-Town. But there are about two days every fall and every spring when it’s warm but still cool and breezy and clean-smelling, and this was one of them. Sweater weather.

“Sixty-five days without food, Ollie,” Alex said. “Sixty-five days.” He was talking about the Irish hunger striker, Bobby Sands. But I had woken up thinking about my mom and everything that had happened the last time she went to bed, and I didn’t want to talk about Bobby Sands.

I kept walking. Alex was doing what Alex does when he has to get someplace, which is a combination of vaulting over trash cans, balancing on ledges, and walking on his hands. It’s difficult to have a conversation with a person doing that.

He tried again. “He has to be on a waterbed now, his bones are so fragile.”

“Let’s not be macabre,” I said, in my trademark perfect imitation of his mom. In fact, it was exactly what Linda had said when she’d first found out that Alex and I were interested in the hunger strikers. The secret to sounding exactly like Linda is to keep your teeth shut even when you are talking. Open your mouth, but not your teeth, and you’ll sound exactly like her, too.

The trademark imitation worked. First Alex looked surprised, then he shot me a furious look and sped up so he was walking way in front of me. I watched him disappear around the corner onto West Broadway, his lightsaber in front of him, and I fell back to walk with Richard.

Richard was using his tube as a staff. He is the slowest walker of anyone I’ve ever met. Richard does everything slowly. His mother says it’s because he is deeply thoughtful, but even she gets annoyed if they’re in a hurry.

“Who was that big guy on your block?” he asked me.

I shook my head; I had no idea what he was talking about.

“He was stopping people, to ask questions. He tried to show us something, but we ran.”

That was weird. “Creeper?”

“Probably not. We just didn’t feel like getting into it.” That meant Alex hadn’t felt like getting into it. He doesn’t like to stop.

“How come you slept at Alex’s house?” Linda wasn’t usually a fan of the school-night sleepover.

“My mom had to go to a meeting.” Richard’s mother is a professor. She is very politically active.

“Was his dad there?” Richard shook his head no; Alex’s dad travels for business all the time.“What’d you have for dinner?”

This was an important question because Linda is always on a diet. I don’t see why she bothers because she always looks the same, but that is the number-one reason why it is terrible to sleep at Alex’s house. At least when Linda was doing Atkins they had steak and hamburgers all the time, even if you didn’t get a bun. It had been pretty hard on Alex since she’d started Pritikin, though.

I privately thought Alex was interested in Bobby Sands because he was always hungry. I wasn’t sure why I was interested in Bobby Sands.

“We had vegetable soup, and Linda counted out eight crackers.” Richard talks slowly, too. “Afterwards”—he grimaced—“there was cottage cheese. With sugar-free jam.”

Cottage cheese is punishment, not food. It is certainly not dessert.

Richard and I crossed onto Bedford. It’s so narrow you have to go single file, which makes it hard to talk, but Richard never minds a long silence. I have to say, he is a very comfortable person.

I was distracted, too wrapped up in my own thoughts even to ask to pet people’s dogs. That morning, I’d gone into my mom’s room to say goodbye. I’d hoped that she’d tell me her plans for the day, or some news about my dad, but she’d barely opened her eyes. Even her hair looked tired.

Friday night, the reading lamp had made all the clutter in her room look cozy and nestlike. In the morning, though, the sunlight leaking in through the sheets over the window washed everything out, making the room look grey and dirty. On my way home from the park on Saturday, I’d stopped to get her favorite pasta from Luizzi’s, but she hadn’t eaten more than a bite, and the sight of the cold, hard spaghetti sitting in a puddle of congealed clam sauce had made my stomach flip. Afterward, I went back into my own room and made my bed.

Alex was ahead of us, dragging his lightsaber across a brownstone’s wrought-iron front gate. Winter pale and extra-skinny, he was wearing the red Kool-Aid T-shirt he usually lent me when I slept over at his house. It was getting to be a little too small for him, even though it was still a little too big for me.

All the Greys on Greene Street

All the Greys on Greene Street